Written by Jen Baily

Edited by Anna Feitzinger

Illustration by Sydney Wyatt

As I sit with earplugs in my ears, a tight velcro cap and a firmly secured helmet on my head, my right hand and right eye twitch of their own accord while the magnetic field creates a drumroll sensation two inches into my skull. It only lasts three seconds, but repeats over twenty minutes until my session is complete. This will continue every day for a month, then twice a week for two months.

As someone with drug-resistant major depressive disorder (MDD), there are few options available to treat my symptoms, especially after being on the maximum doses of 5 different medications over the last few years. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), colloquially known as shock therapy, is often used as a last resort; however, it can cause severe memory loss and brain damage. Anecdotally, I’ve known friends that have undergone ECT who were never the same, which took it off the table for me. It wasn’t until meeting a psychiatrist to manage my medications that I learned about deep transcranial magnetic stimulation (dTMS), and how it is a non-invasive procedure for which I was a good candidate.

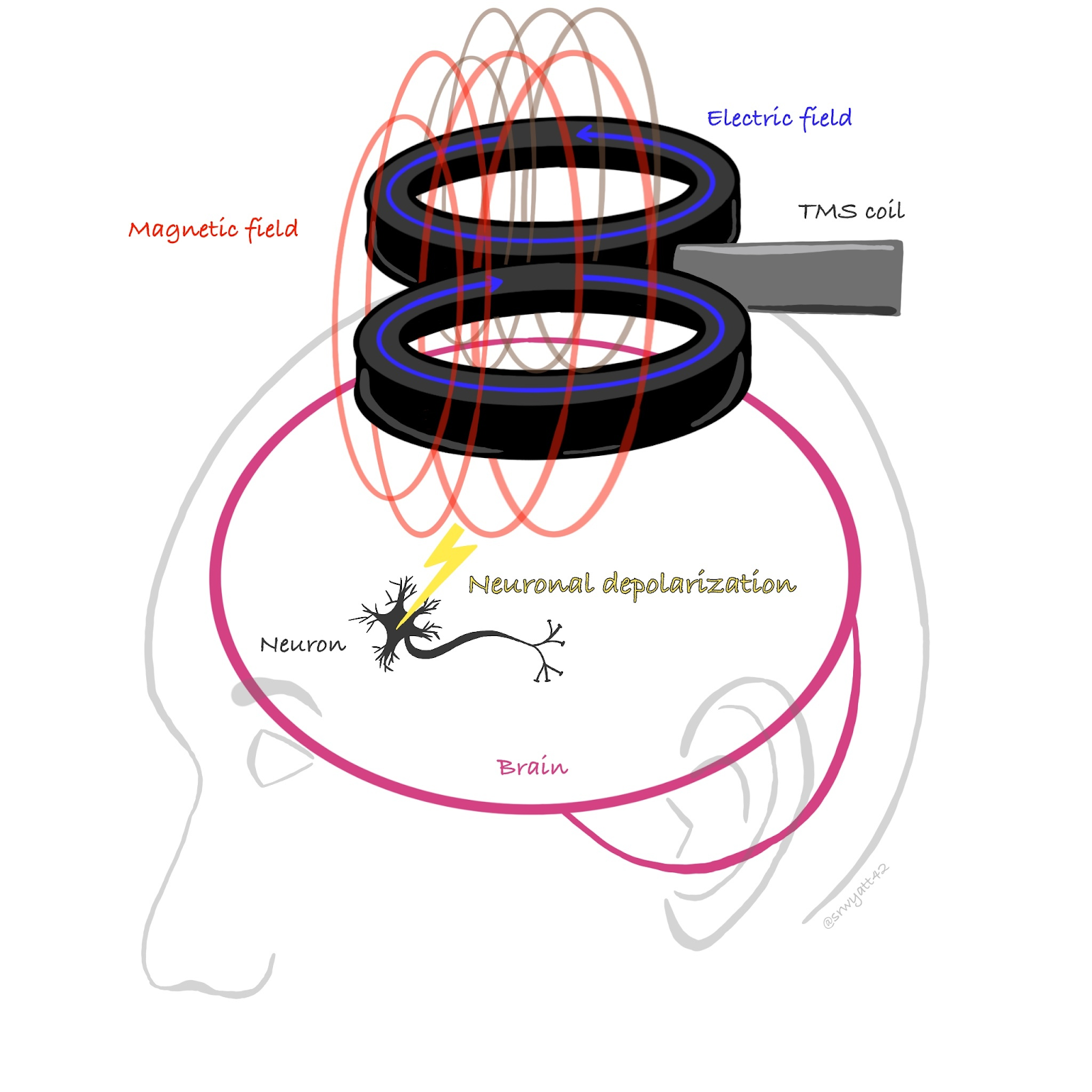

From the paragraphs above, as well as the name dTMS, you probably get the idea that dTMS is a deep, skull-penetrating magnetic pulse. How can this be used specifically to treat depression? The idea behind dTMS is to use this magnetic field to affect neurons, which act as conductors.

In 1985, Anthony Barker and his associates produced the first transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) device. It was based on Faraday’s discovery in 1881, where a magnetic field was created by running electricity through a coil. By rapidly switching the magnetic field’s intensity or direction, you can depolarize neurons in a specific region of the brain. Though not fully fleshed out, it is thought that increasing the neural activity in the mood center of the brain, the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), may be the mechanism by which dTMS alleviates symptoms of depression.

The treatment targets the DLPFC on the right side of your head. The psychiatrist or technician finds the DLPFC by applying magnetic pulses until your hands begin to twitch, indicating the magnetic fields have reached the motor cortex. This allows the doctors to position the helmet containing the magnets over the DLPFC and to induce the firing of neurons in the area. dTMS is akin to Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) machine, except dTMS is specialized to stimulate the brain while TENS is inTENded (pun) to reduce pain. Nevertheless, the principle of manipulating the nervous system to the benefit of the patient remains the same. The neural activity caused by the dTMS magnets increases expression of brain derived growth factor (BDGF), increased neural outgrowth and connectivity in rats (Paus, 2011), and showed a major elevation in mood of patients relative to a placebo treatment during clinical trials (Yates, 2016). BDGF accomplishes these tasks due to its role in development, maturation, and maintenance of neurons.

By increasing the activity of neurons in the brain regions typically affected in patients with MDD, a burst of growth is thought to follow the acute/intense phase of treatment, when a patient is going in every day. During the second phase, where a patient is treated a few times a week, the activity is thought to be maintained while the brain adjusts. Relative to previous models of the TMS technology, deep TMS has an excitingly high “remission rate of 32.6 in active deep TMS (vs 14.6 sham treatment)” (Levkovitz, 2015). Remission of MDD is typically thought to be a significant decrease in depressive symptoms for longer than 4-6 months (Frank, 1991). While this may seem like a low number, for someone suffering from depression, any reduction in symptoms can be helpful, and full remission of symptoms can allow someone to function normally. For the third of patients who’ve never felt relief, this is life-changing.

After extensive studies on rats and clinical trials on humans, the FDA approved dTMS use for patients who had failed 2 or more medications during their current episode of depression. Because dTMS is not a medication, simply a locally applied magnetic field, it is without the usual side effects such as “weight gain, sexual dysfunction, nausea, tremors, dry mouth, diarrhea, headaches, constipation, sweating, sleepiness or anxiety” that are associated with antidepressant use (History of dTMS). What’s wonderful, in my opinion, is that the patient can drive to and from their appointment. There are minimal side effects that usually dissolve shortly after a treatment session. Apart from the super magnets being quite noisy, the strangeness of the feeling itself, and occasionally scalp tenderness, it really is an amazing option for patients with drug-resistant MDD.

If dTMS is such a wonder “cure” for depression and anxiety related disorders, 1) why haven’t more people heard of it and 2) why don’t more people utilize this technology? To address question one, I’ll quote my lovely psychiatrist, “stigma.” There is a certain stigma associated with a daily treatment regime, especially one that requires transportation to a clinic. Though effective, it is a new technology and can often be lumped together with ECT in the public eye, which can be a traumatic experience for patients. To address question two, dTMS is very expensive. UC student health insurance is quite good for mental health services, but even then, I had to fail out of 5 medications and rate at a specific level of depressive symptoms prior to any coverage for almost a year. Failing out of medications involved either severe side effects or lack of effect for 16 weeks of treatment. If the insurance company doesn’t think you’ve gone hard enough for long enough, they can request that you take higher doses of medication prior to approval. All this is associated with the side effects mentioned previously, and during this time the patient is suffering. Additionally, a patient may be suffering to the point of suicidal ideation, but is functional enough to score below the required threshold on a PHQ-9 form. If a patient battling with depression must be their own advocate while on heavy medications and experiencing symptoms, getting to a place where dTMS is possible can be difficult. However, things are starting to change for the better.

As dTMS becomes a more mainstream treatment option, more and more patients are seeking it out to ameliorate their symptoms. Along with the patients themselves feeling better, those in their lives are able to notice improvements. My own partner told me that I was able to carry a conversation for significantly longer after a month of treatment relative to my depressive episode. As more and more people notice the impact that this treatment has on their loved ones, word will spread. Additionally, within the past 10 years, mental health stigma has significantly decreased. Now, I can openly talk about my own experience with minimal impact to my career prospects, and am still viewed as a functional and contributing member to my community.

In learning about dTMS for my own sake, I was amazed by the scientific literature behind it. The technology brings together physics and physicians, neuroscientists and patients. Through their creative and thorough research, hope has been brought to many suffering with MDD, myself included. If you or someone you know has struggled with a severe depressive episode, perhaps now is a good time to discuss dTMS with your physician or other new technologies as treatment options. And always remember, reach out if you need help. You’ll be surprised by how many people and how many treatments out there can help.

On campus services – UCD specific

https://leadership.ucdavis.edu/strategic-plan/task-forces/mental-health

- Individual counseling

- Couples counseling

- Group therapy

- Skills groups

- Case management

- Career counseling

- Outreach to the campus community

They only work if you use them.

Partial Hospitalization and Intensive Outpatient Programs

Group therapy at a hospital location, often using cognitive behavioral therapy, with access to on-call psychiatrist and nurse.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

We can all help prevent suicide. The Lifeline provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress, prevention and crisis resources for you or your loved ones, and best practices for professionals.

Online Chat – Lifeline

1-800-273-8255

“Warm Line” – Talk to trained listeners before a crisis: Visit http://www.warmline.org/ to find the number for your area.

Talk to trained listeners over text: https://www.crisistextline.org/

References

http://www.brainefit.net/history-of-tms.html

Yates E, Balu G. Deep Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: A Promising Drug-Free Treatment Modality in the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain. Del Med J. 2016;88(3):90‐92.

Johnson, Mark. “Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation: Mechanisms, Clinical Application and Evidence.” Reviews in pain vol. 1,1 (2007): 7-11. doi:10.1177/204946370700100103

Levkovitz, Y., Isserles, M., Padberg, F., Lisanby, S. H., Bystritsky, A., Xia, G., … Zangen, A. (2015). Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depression: a prospective multicenter randomized controlled trial. World psychiatry : official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 14(1), 64–73. doi:10.1002/wps.20199

Tomáš Paus Manuel A. Castro‐Alamancos Michael Petrides (2011). Cortico‐cortical connectivity of the human mid‐dorsolateral frontal cortex and its modulation by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. European Journal of Neuroscience. 14(8), 1405-1411. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01757.x

Frank E, Prien RF, Jarrett RB, Keller MB, Kupfer DJ, Lavori PW, Rush AJ, Weissman MM. Conceptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery, relapse, and recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991 Sep; 48(9):851-5.