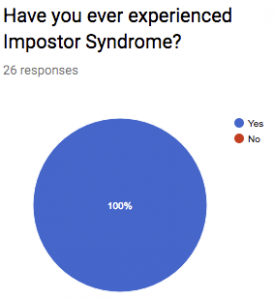

All 26 BMCDB graduate student respondents self-identified as having experienced impostor syndrome

Author: Linda Ma

Impostor syndrome has been experienced by most students and academics to some degree, but rarely openly addressed. It is something that I have struggled with throughout my entire academic journey. My peers had always seemed so put together, so self-assured. In the meantime, I never felt good enough, never deserving enough. In short, I felt like an impostor.

Impostor syndrome is defined as being plagued by constant self-doubt and the fear of being found out as an ‘intellectual fraud’ (Villwock et al., 2016). Dr. Terrance R. Mayes, Associate Vice Chancellor of Diversity and Inclusion at UCI characterizes impostor syndrome as attributing one’s success to luck, to connections, to being in the right place at the right time, rather than due to one’s own merit.

I couldn’t put a name to my own feelings of impostor syndrome until the summer of my senior year in undergrad when I took part in a summer research program. The program coordinator sat us all down in a lecture hall and proceeded to describe me to a tee. In that moment, everything clicked.

Still, there was a stigma about discussing impostor syndrome with my peers. Putting a name to my feelings didn’t mean an immediate cure. In my first quarter of graduate school, more than ever, I was plagued by feelings of self-doubt. Balancing the course load with lab rotations was overwhelming, and I always felt like a disappointment. Nothing I ever did felt good enough.

Given how impostor syndrome is usually discussed behind closed doors, I was pleasantly surprised by how many students and faculty were willing to openly share their experiences with me.

I circulated an anonymous survey to the BMCDB graduate students and 100% of the 26 respondents reported that they have experienced imposter syndrome in some form. Respondents ranged from first years to sixth years.

While chatting with Dr. Steve Lee from Graduate Studies, he brought the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS) to my attention. CIPS was developed by an Atlanta based psychologist, Dr. Pauline Rose Clance. CIPS numbers range from 20 to 100, with those scoring higher than 80 experiencing intense IP (impostor phenomenon) tendencies. Completing this short evaluation does not constitute an official diagnosis but may put your impostor syndrome into perspective. Taking the assessment helped me confirm the intense impostor syndrome that I’ve been experiencing for most of my life. Moving forward, I have found myself being a lot more open with expressing these feelings to my PI. I would be interested in knowing how members of the UC Davis and broader scientific community fall on this scale.

I was surprised to find that Dr. Anna La Torre (Assistant Professor), and Dr. J. Clark Lagarias (National Academy of Sciences Member, Distinguished Professor, and current BMCDB Chair) have both struggled with impostor syndrome. Strangely, this was reassuring to me that such successful professors have grappled with the same issues that I have been suffering from.

Dr. La Torre brought the following to my attention, “It affects women more than men and individuals from underrepresented groups are even more susceptible. So, if you are like me, a woman and a minority, chances are that you feel like a fraud.”

First year Abby Primack voiced similar views that “women, people of color, and other marginalized communities” especially feel this.

It’s important that graduate students and the broader scientific community know that impostor syndrome is common, and there should be no shame in owning up to it and having an open dialogue with your peers.

I have been coping with my impostor syndrome by confiding my fears to members of my cohort and those close to me. Secondly, my PI has been an unwavering force of support.

A common theme among the faculty and students that I surveyed was that talking about our experiences with impostor syndrome was key in overcoming or managing our feelings.

Students surveyed were all very adamant about talking to professors, colleagues, advisors, older students, and “people who believe in you and support you and can bring you up when you doubt yourself.”

One third year student quipped that you need to “fake it ‘til you make it.”

When second year Anna Feitzinger gets overwhelmed and intimidated by graduate school she takes a deep breath and reminds herself of how far she has come, and that she got into graduate school for a reason.

An anonymous fourth-year student advised, “Make a habit of being courageous, taking risks and working outside of your comfort zone. You will likely realize that the community is more supportive and less critical of your competence than you are.”

Sixth year Matt Blain-Hartung says that the “only way to overcome this is to… push forward and stick up for yourself. Eventually you will win some arguments with your boss/ post-docs and remember that you deserve to be here.”

For Dr. Lagarias, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and support from family and friends have been key resources. “It is easy to lose perspective when we are all trained to over-hype our own accomplishments to ‘be successful’.”

Dr. Lee believes that a balance must be struck between being too arrogant and being too encumbered by one’s impostor syndrome to be motivated.

However, there is no one-size-fits-all way to manage one’s self-doubt. Coping mechanisms which work for one individual may not work for another. It is important to find what works for you.

Dr. La Torre said something that really resonated with me and many of the student survey respondents, “Avoid comparing yourself with others. We are surrounded by amazing, talented and successful people. You don’t need to be Einstein to achieve your goals, so stop comparing yourself to that person. It’s important to admit that you had some role in your own successes. It was not all pure luck, and nobody belongs here more than you.”

This article by no means serves as a ‘how to guide’ for overcoming impostor syndrome. I mean it only as a stepping stone to an open discussion about something that most of us suffer from but are too afraid to talk about. Perhaps there is a way to bolster our scientific community and address the mental health issues that we face as academics. We, the meek scientists, must stop keeping our fears bottled up.

Edited by: Sharon Lee

Additional resources:

References

Villwock, J.A., Sobin, L.B., Koester, L.A., and Harris, T.M. (2016). Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. International Journal of Medical Education 7, 364-369.