Written by Keith Fraga

Edited by Mikaela Louie

Psychedelic drugs are often taboo in US culture particularly since their extensive criminalization in 1970. Substances like LSD, MDMA, DMT, and those derived from fungi like psilocybin, are drugs known to have hallucinogenic effects on humans. The ability of these substances to produce mind-altering experiences lead to massive efforts to control their study and use.

However, restrictive policies surrounding psychoactive and other mind-altering substances may be changing. For example, cannabis is undergoing rapid social and legal acceptance in the US. The City of Oakland legalized the recreational use of magic mushrooms in June, another potent hallucinogenic. Substances such as ayahuasca have a long history as a traditional medicine. Whatever impact psychedelics have on treating debilitating mental illnesses deserves experimental study and mechanistic understanding. Indeed, psychedelics are in several clinical trials to treat various mental illnesses, like depression, anxiety, PTSD, with the potential to be applied to many more mental health conditions. UC Davis researchers recently published an article in Cell on a study of psychedelics’ effects on neural plasticity.

Diving into the literature, I wanted to answer a few specific questions. What is the history of psychedelic research? Where did restrictive policies surrounding psychedelics come from in the first place? What has contributed to the thawing of restrictions on clinical psychedelic use ? How has biology and neuroscience changed our understanding of these substances? And lastly, what do we not know and where should we be cautious?

HISTORY

The history of psychedelic drugs help us understand their possible future. Psychedelics refer to many substances, and naturally occurring psychedelics such as psilocybin or ayahuasca have been consumed by humans for centuries. Others are more recent in human history, being chemically synthesized in the late/early 19th-20th centuries. When consumed, psychedelics generally cause an altered state of perception. Often these altered states affect tethers to reality, mirroring what happens in psychosis. The history and story of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) is an important example of the use and study of psychedelic drugs.

LSD was first synthesized by Swiss scientist Albert Hofmann in 1938. Hofmann set out to synthesize compounds that could be used for blood vessel constriction, which could help in medical applications to reduce blood loss. After accidental contact with LSD, Hofmann found that this compound had hallucinogenic properties.

Hofmann self-administered doses of LSD to test and observe its effects, becoming convinced of LSD’s potency to address mental illness. Hofmann contributed to the spread of LSD from doctor to doctor, making its way to the US. It was quickly found that LSD had potent therapeutic effects for treating various psychological conditions and became wildly presubscribed by therapists across the US and Europe.

USE AND REGULATION IN THE UNITED STATES

An important aspect to the rise in LSD usage was the prescription and research by independent, unregulated clinics and therapists. In this unregulated climate, LSD found its way out of the laboratory and into the 1960s US counter-culture. The culture around psychedelic research and usage at this time was very exploratory. As with the initial discovery and subsequent spread of LSD, therapists and researchers self-experimented and shared these compounds without discretion.

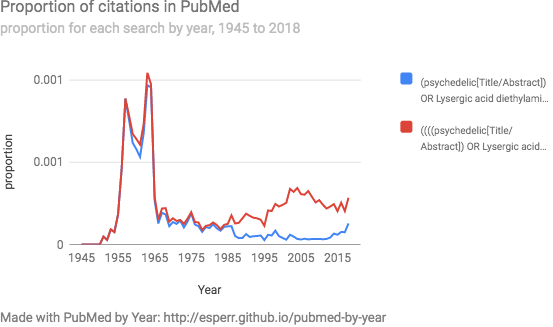

The obvious potent effects of LSD spurred a generation’s worth of compelling, rigorous research. Figure 1, shown below, depicts the relative citation rate for the terms “psychedelic” or “lysergic acid diethylamide” in any journal article title/abstract. The years between 1950-1970 can be called the “golden-age” of clinical and basic research on uses for LSD. During this period, much was learned about LSD’s effects on human psychology, crucial observations on the aspects of psychedelic “trips”, effective uses of LSD in psychedelic assisted therapy, all of which are now being re-examined with modern medical and biological methods.

Figure 1: Citation rate for words “psychedelic” or “Lysergeic acid diethylamide” in journal article title/abstracts. The data series in blue is just for “psychedelic” or “Lysergeic acid diethylamide”, while the red series is a separate search with additional search terms for other psychedelic substances. Find the interactive version here.

It is also clear from Figure 1 is the “golden-age” of LSD research rapidly came to an end. In response to growing concerns for unregulated, unethical use of LSD, the Food and Drug Administration adopted new policies restricting the use, possession, and manufacturing of these drugs. A series of legal policies were installed in the ‘60s to curtail the use, possession, manufacturing, and research into these compounds, culminating in the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in 1970. The CSA is the legal authority that established the Schedule system for controlled substances. Schedule I is the most restrictive category of compounds. With strict policies and massive legal consequences for inappropriate use of these substances, many researchers and therapists in the field ceased their work.

THAWING OF RESTRICTIONS ON PSYCHEDELIC RESEARCH

It is difficult to identify a singular cause for the increase in interest and research on psychedelics. That being said, I find two specific developments particularly informative to the growing acceptance of psychedelic research. First is the research on how psychedelics can improve the quality of life for patients with life-threatening disease or terminal illness. Patients with life-threatening diseases, terminal illness, and associated chronic pain experience lower quality of life, higher rates of depression, and lower life-expectancy. While researching for this article, I found the following interview with Michael Pollan, a journalist who studies the impacts of psychedelics and their potential growing role in society. In this interview, he relates what sparked his interest in therapeutic use of psychedelics was their ability to improve the mental health of terminally ill patients. Numerous recent studies and reviews have recently contributed to this area of research. Psychedelics in end-of-life care was actually studied in the 60’s, and it is now being revived. Current research on therapeutic effects of psychedelics has demonstrated they can dispel anxiety, fear, and despair in these patients safely, and social taboos and legal policies are slowly changing in order to increase access and study of these benefits.

Psychedelic assisted therapy is also being explored for an array of mental health conditions. Numerous psychotherapy drug trials currently ongoing. The MultiDisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is a central scientific research coalition propeling psychotherapy trials forward. MAPS independently supports trials for psychotherapy with a wide array of substances to tackle a diverse set of mental health conditions. Specifically, MAPS is currently working with the FDA for MDMA assisted psycho-therapy.

Psychedelic assisted psychotherapy presents an alternative therapy regimen for mental illness in part because of the global effects psychedelics have in the brain. A significant hypothesis in this field is psychedelics and psychiatric medications address mental illness at different scales. Psychiatric medications, like antidepressants, offer to rectify chemical and functional imbalances in the brain. These often target specific neuro-transmitter/receptor imbalances. However, psychedelics impact brain activity at a systems level, disrupting default neural networks and activating connections between disparate regions of the brain. The golden-age of psychedelic research in ‘60s intuitively reached many of these ideas concerning the global effects in the brain psychedelics have. With modern developments in science, medicine, and biology, researchers can interrogate psychedelic compounds’ effects on brain function at greater resolution.

A BIOLOGICAL MAGNIFYING GLASS TO PSYCHEDELICS

A significant motivation of this article is a study by a team of UC Davis scientists studying the effects that a battery of psychedelic drugs have on structure and dynamics of neurons. This study experimentally demonstrated that many psychedelic compounds promote neurons to make new synapses, growth of new neuron axons, and altered neurophysiological functionality. In part, this is why psychedelic compounds are termed by the authors of this study “psychoplastogens” for their ability to promote plasticity at the level of the brain. These investigators also experimentally tested mechanistic models for how these large-scale structural and functional changes in response to psychedelics. Investigations similar to the UC Davis study represent how advanced techniques in biology can garner quantitative insights into the mode of action for these potent compounds.

A greater understanding of how psychedelics functionally work in the brain can lead to the generation of new compounds that have similar functional effects demonstrated in the above study, with the idea being these newly designed compounds may induce similar subjective experiences, or “trips”. In other words, the generation of novel “psychoplastogens” is possible when we learn more about what determines their function in the brain. Alternatively, psychoplastogens can be used to perturb aspects of the brain to piece together the mechanisms for subjective experience. Biology has a rich tradition of using tools to perturb a biological system and measuring its output to uncover the mechanisms that make it work in the first place. Psychedelics can serve a similar role in potentially understanding perception, cognition, and consciousness.

CAUTIONARY TALES

Nearly every editorial, podcast, or interview I have heard on this subject includes strong cautionary tales. Psychoactive drugs can have unintended consequences.The mind-altering capabilities for these drugs are so potent that they may do more harm than good for some people, which is one reason why I am particularly excited about the prospect of trained therapists guiding a patient’s trip. How the chemistry of these molecules and their therapeutic use come together to help people is an exciting new venture in medicine.