Written By: Will Louie

Edited By: Nina Sibonae Cueva

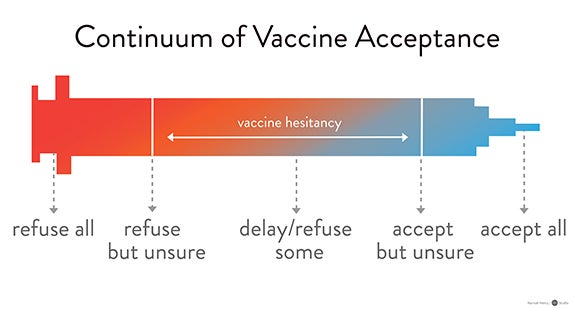

It is flu season, so I hope you have all gotten your flu shots! Vaccinations are arguably one of the most game-changing medical achievements of human civilization. Developed countries enjoy the eradication and suppression of some of the deadliest viral and bacterial diseases. However, since the publication of the original study fraudulently linking the Mumps, Measles, Rubella (MMR) vaccine to autism, the anti-vax movement is on the rise in the United States. And while scientists focus on the black-and-white of whether to vaccinate when debunking this claim, vaccine-hesitant people are still left in the middle. This group does not flat out reject vaccines, but are either fearful about the side effects, considering alternative vaccination schedules, or just distrustful of medicine in general. It is critical that we as scientists empathize and address the sources of hesitancy, a phenomenon that describes reluctance but not complete opposition to vaccination.

Many infectious diseases that terrorized our ancestors are but a memory thanks to mass vaccination. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the incidence of many infectious diseases have dropped by over 90% since the implementation of quality-controlled vaccines. Globally eradicating smallpox in 1980 was only possible through mass vaccination. Famously, Jonas Salk’s first successful polio vaccine in 1955 was immensely successful in pioneering mass vaccination, as millions of American families volunteered their children in Salk’s government-funded vaccine trials. Parents truly felt they contributed to a greater good, and the rapid transition from fears of losing their children to the disease within a single afternoon to near eradication of polio incidence highlighted an immense payoff in trust of a government program. Following worldwide administration, polio has been nearly eradicated, with sporadic transmission confined to inaccessible regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Despite these success stories, vaccine hesitancy has persisted, and understanding the perspective of those who are vaccine hesitant is imperative to improving our communication with the public.

Fears about autism

The most resilient debunked argument against vaccinating children is the fear that vaccines cause autism. Although the study was retracted, the damage was already done: this argument lingers among social media groups and anti-vax blogs. More worrisome is not that people still believe this unsupported causal relationship, but that anti-vaxxers prioritize preventing autism over preventing potentially deadly diseases. The fear is unfounded and counters collective efforts to destigmatize physical and mental disabilities. While the universal consensus among scientists is that no causation between vaccines and autism exists, it is uncertain whether this rebuttal alone is sufficient. Many vaccine-hesitant parents are still unsure whether this autism link is truly debunked, thanks to the mass amounts of information and disinformation circulating on the internet. We should also delineate the differences in health outcomes between autism spectrum and deadly infectious diseases. Even if this were true, the benefits outweigh the risks, and marginalizing those who are actually on the spectrum is not helpful. As scientists, we must improve our communication to clearly share the benefits and real risks of vaccination without alienating an already marginalized population. Shifting our focus from sole denial of MMR-autism causation to an emphasis that the benefits of MMR protection are worth the risks of side effects, addresses parental concerns for their children’s health in a non-judgemental manner.

Fears about government ethics and transparency

We all have a favorite conspiracy theory; I love the claim that “pigeons are not birds but actually government surveillance drones implemented to spy on urban civilian life” (citation not needed). Likewise, there is no shortage of conspiracy theories regarding vaccines. Moreover, there is a striking overlap between people who believe in conspiracy theories and those who are skeptical of vaccines. However, one cannot help being sympathetic to groups who are distrustful of government. After all, the U.S. government’s track record for medical ethics and transparency has been less than stellar. From the Tuskegee syphilis experiments targeting African American males on the domestic front to the CIA’s fake vaccination program in Pakistan as a cover for hunting Osama bin Laden on the international front, it is no surprise that many people are skeptical of government-mandated vaccine compliance. While there is still a giant chasm between outlandish chemtrail conspiracies and a real concern over government regulation or deregulation of vaccine administration, we need better ways to communicate the differences. Those who are vaccine-hesitant often struggle to separate distrust in the business practices of our corporate overlords from distrust in the science itself. Public health professionals and medical researchers need to bolster efforts at communicating the risks, benefits, and evidence for vaccines in a transparent and assuring manner. Most importantly, however, is the need to repair trust between the government and the people, a problem that transcends the anti-vax movement.

Fears about Big Pharma

Similar to the distrust in government is the distrust in companies that profit from vaccine development and distribution. It is easy to paint the pharmaceutical industry as the villain, because it is true in many cases. Examples of corporate greed taking priority over civilian health are all too numerous: former Turing CEO Mark Shkreli’s 5000% markup on the drug Daraprim (arguably a catalyst for discovery of the even more sinister predatory price gouging by Valeant Pharmaceuticals); Purdue Pharma’s role in fueling the opioid crisis; and Bayer knowingly selling HIV-tainted products to developing countries. As a self-proclaimed jaded millennial, I am not surprised that there are people, paranoid or misinformed, who see vaccines as just another case of Big Pharma capitalizing on a medical necessity to maximize profits. But Big Pharma generally doesn’t profit from vaccines. The cost of an annual flu shot ranges from $0 to $50 depending on your medical provider, while other vaccines like the intravenous polio vaccine are being given to children in developing countries for free, because even they understand the long term benefits of mass vaccination. The scientific community must separate fact from fiction when it comes to Big Pharma’s games, and effectively communicate that getting vaccinated doesn’t really affect their bottom line.

How do we come in?

It is important to note that anti-vaxxers are a vocal minority group. It is unlikely that any amount of evidence or communication will convince those deep in the anti-vax camp, but we can help those who are undecided. The vast majority of Americans do support vaccines and vaccination rates in the U.S. are still high, but they can be improved. Recent years have seen a rise in measles cases, traceable to anti-vax communities. While measles vaccination rates in the U.S. have remained at approximately 91% from 2013 to 2017, the required vaccination rates to confer herd immunity to measles has been estimated to be >95%. Importantly, most parents just want what is best for their kids. However, when they decide not to vaccinate their children, they are not just making a decision for their children, they are making a decision for their community. Immunocompromised individuals as well as children too young to get the particular vaccine rely entirely on herd immunity,. Thus vaccination rates for highly contagious measles need to be higher to provide effective herd immunity. As scientists, we can understand these statistics and translate them to the vaccine-hesitant group for the benefit of all.

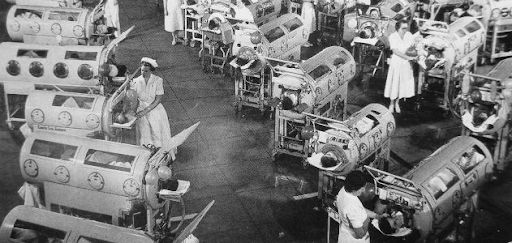

Facts, evidence, and rationalism are the bread and butter of scientists, but this does not always translate well to the layperson. As seen in segments of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver and Full Frontal with Samantha Bee, comedy is a great way to relay information about vaccines. This is accompanied by the realization that emotional anecdotes about children who suffer from vaccine-preventable diseases connect to parents much more effectively than do facts and figures. As much as I hate to admit it, my beautiful PCR gels and stunning figures of antibody titers are less impactful than a commercial for polio vaccination showing children confined to the Iron Lung (picture below) after being afflicted with polio. As scientists, it is difficult to leave the bench behind and participate in activism and communication. It is a constant struggle to communicate science to the public in an amicable and informative manner. Rather than dismiss all concerns about vaccines, we should constantly improve our communication to be rational but relatable, confident but approachable, stern but empathetic. Fighting vaccine hesitancy is an uphill but winnable fight that will pay off with improved means of scientific communication.

Smithsonian Magazine, 1952